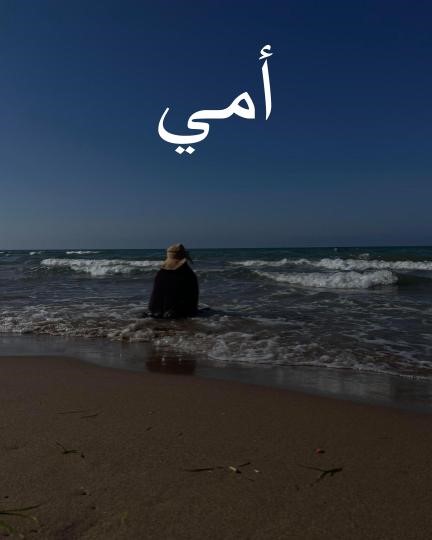

Fictionalized depiction of a story of a prisoner in Saydnaya Prison in Damascus, Syria. A prison widely known as the “Human Slaughterhouse” for its torture, abuse, and extreme violations of human rights against any who opposed the Assad regime and were arrested illegally and held without trial. Many were freed when Syria was liberated on December 8th, 2024. Thousands more remain trapped or missing.

This story contains imprisonment, sexual and physical abuse, beatings, torture, blood, confinement, PTSD

Drip. Drip.

He snaps out of his reverie, pulls and rips his arms away from the soldier holding him up, stumbling against the wall as he tries to get his bearings. Freedom was not a word uttered here. His eyes catch on the flag stitched on the upper right sleeve of one of the soldiers’ green uniforms. Instead of the usual red stripe at the top and the two green stars in the middle, he sees something he hasn’t witnessed since before entering this place. Like how he imagined seeing the sky again. Both familiar and unfamiliar. The flag on the uniform was green at the top with three red stars in the middle. He stared and stared. The independence flag. The freedom flag. It was a trick. It had to be. They were testing him. Right?

He begins to hyperventilate, his breaths becoming more shallow by the second, his chest tightening to the point of pain once more, and his movements become frantic as they try to grab him again. He swats their arms away, but they barely budge, and begs them to let him go, wincing from the loudness of his voice, promising he wouldn’t escape, wouldn’t leave, just let him go back into his cell—this wasn’t the first time they tried to test him, you see. He had ‘failed’ the first few times, but quickly learned the consequences. The quiet cell was a haven compared to that padded red room the guards used for their investigations, red because of the blood that never gets washed out and padded to suffocate the prisoners in there further. He realized early on it wasn’t actually soundproof when they dragged a woman in there after his interrogation was done, tossing him back into his cell with newer wounds than what he left with. Nothing is soundproof in this place. Can you hear him?

He turns around now, ready to jump back down, when the soldiers with the pretend green flag pull him back and spin him around to face them, holding him in place. He failed again. He panics, thrashing against them experiencing the flashbacks he’s tried so hard to repress. The beating. The pole. The electrocution. The water. All of it comes at once and he’s drowning. The memories are everywhere—grabbing at him, strangling him. The air leaves his lungs as he struggles to stay present. To breathe.

Drip.

Maybe they’ll let him go, just this once. He begins to plead—each of his arms held firmly again by the soldiers who grabbed him—his voice hoarse and raspy from disuse. The only sound he was used to making were the screams of agony that would tear from his throat and remain trapped in the red room. In his frenzy to tear away from them, he accidentally looks up at their faces, forgetting his personal rule to avoid eye contact, and finds droplets. He stops talking—screaming, begging, yelling—as he blinks at their tear-filled eyes. He looks around. There’s two others with tears running down their faces. He hears his fast and quick breaths and more shouts from down the hallway.

The soldier holding him tightens his grip, enough to remind him of where he was. That this was real. The soldier, choking back his tears, swears by God that he is not with Assad. He is not a prison guard. He recites a verse of victory. From the Quran. The man’s heart skips a beat as he recognizes it and a sob escapes his throat. It’s not a test. He didn’t fail. The green flag is real. He doesn’t push it down this time. Racking, heaving sobs break free from his lungs—they would’ve brought him to his knees had he not been held up by another. He remembers now what he recited on that day. It was the Quran. They beat him for it. He remembers. The doubt that had crept in his mind and the fear that had seized his lungs earlier seep away as the soldier brings him close and hugs him like a forgotten brother. The man—weeping—clutches desperately back, burying his head into the soldier’s shoulders, letting the words of God wash over him like a soothing balm, temporarily keeping the other memories at bay.

His tears begin to slow, and his cries quiet down enough for him to stand straighter. The soldier loosens his embrace to loop his arms under the man’s, glancing back at the cell. The soldier’s face pales at what he sees, and the man tries to turn back, catching a glimpse of his small and dark holding. Once more, just to see it in the light. Something unfit even for an animal, with lines engraved all over the walls. Lines he had carved out with a broken nail he found to try to track the time in the beginning. They eventually found out what he was doing and took away the nail. He got a broken wrist for that. The lines look more like the scratches and clawings of a trapped creature in the light. How ironic. The soldiers—one with his arm under the man’s shoulders, another with his arm around the man’s waist—quickly turn him away and help him move forward. He didn’t get to see where the droplets were coming from. His legs keep stumbling over themselves, too cramped. His body too adjusted to the captivity and unused to moving freely. Free. What a strange word. Don’t you think so too?

Drip. Drip. Drip.

The soldiers stay with him, helping him limp down the hallway, ignoring the metallic smell laying heavily in the air, creating a sticky sort of fog, similar to that of his cell—the lack of windows and filtration were meant to slowly siphon the clean air a prisoner’s lungs entered the jail with, ripping you of everything and leaving you with nothing. They hastily continue past the newly emptied prison cells, their doors still swinging open, nearly stepping on the brownish-reddish puddles of unidentifiable liquids that they were trying to avoid on the dirty floor. The puddles looked similar to the water the prison guards would toss him—if he had been quiet for a period of time. The constant side-stepping and rushed movement towards the exit—a long and winding way out it seems—makes the man dizzy as nausea turns his stomach and sweat dots his forehead.

He sneaks a peek at the cells, each with a story more horrifying than the last. The smells of urine and vomit escape the human cages, dark splatters across the walls remind him of the sound of boots crunching on bones. Carved etchings catch his eye, but they were words, not tallies like his, messages of despair, anger, pain, defiance, one after the other until he can hear their screams again—screams that he had learned to block out long ago—and he abruptly turns away, cutting them off before they reach him. Is his body trembling? He furrows his brows and looks at his arms before realizing it isn’t him—it’s the soldier holding him on the right. The one that embraced him. Fury flashes in the soldier’s eyes as he looks at the cells, his body vibrating with the effort to control his thinly veiled outrage at the obvious abuse of the prisoners. At the torture and the lack of dignity. The soldier grits his teeth and directs his gaze forward, the vibrations subsiding even as his jaw remains clenched. The man looks to his left and sees the other two soldiers—all of them appearing to be in their late 20s to early 30s with light eyes and dark hair—pursing their lips, the color draining from their faces as they shake their heads every few steps. Every few cells.

The man swallows the lump that had climbed in his throat and looks down, finally noticing his clothing. A ripped shirt with holes peppered across it hangs off his narrow shoulders and pants covered in dark stains and knife rips reach halfway down his calves. Humiliation colors his cheeks as he tries to separate his body away from the soldiers that freed him, attempting to keep his bare and dirty arms far from their clean clothes, but they only tighten their hold on him, lifting him up. He blinks back the sudden rush of emotion welling in his eyes, and clears his throat. His eyes focus and follow each step his feet take, careful not to trip again.

When they make it to the entrance, he stops abruptly, hesitating. This was real. Is he real? The soldiers stop with him and glance at each other, waiting until he warily nods his head, signaling his readiness. Real. He holds his breath as they step outside and the brightness nearly blinds him. So much brighter than all the prison lights combined. He lets loose the staleness of the murky prison air and breathes in freshness that his lungs don’t recognize—like cut grass and winter rain. Once his eyes adjust again, this time taking longer than before, there are people—his people, he knows now—all around him. Mothers and sons. Fathers and daughters. Grandparents. Wives. Friends. Hugging one another. Sobbing both tears of joy and tears of grief. He stops to take it all in, one of the soldiers on his left letting him go for a moment to speak to another fellow fighter. There were so many of them out here. So much green. Will it be enough to erase all the red?

He sees a young boy—no older than five—come out of the prison behind him, tugging at a woman’s hand, who looks to be his mother but has such deep sorrow written into the lines of her face, so familiar to him he knows she must have been a prisoner too. Take into account the boy’s awe at his surroundings, as if he’s looking at everything for the first time, and his age, it becomes easy to guess the source of her pain. Of her haunted eyes. Do his eyes look the same? Can you tell? The boy points to something in the distance and asks his mother what it is. The man follows the boy’s finger to a tree. The boy doesn’t know what a tree is.

The man feels something warm on his face, spreading across his hollowed out and scarred cheeks. The sun. It heats his face like a welcome from a long lost friend. He’s gotten so used to the dark. To the cold that accompanies it. He looks up and sees the sky. His shoulders begin to relax—he didn’t realize he was standing stiffly. Is it really blue? Perhaps his eyes haven’t yet adjusted properly. He stares at it, his eyes filling with tears—both from the sky’s beauty and from the sun’s light. Perhaps he’s forgotten colors too. Do you also see the blue side of the sky? He asks the soldiers. Confusion writes itself across their features as they take in his question and he begins to internally panic. The last time he asked a question, the prison guards had forced a hot, burning poker to his lips. Now, just as he’s about to take it back, the free soldiers nod slowly, as their confusion lingers with a mix of concern. The man lets loose a tight breath. Free.

Drip. Drip.

His eyebrows scrunch together and he tilts his head as something occurs to him. He doesn’t pause this time as he asks them what happened to Hafez. Was the president captured by this free army of theirs? Did he flee? They all look away. One of them—the one on his right—swallows hard and opens his mouth. Closes it. Opens it again and whispers to him. Hafez has been dead for twenty-four years. It was his son that took over, continuing the tyranny and inciting the revolution, and him that was overthrown. He didn’t know. They tell him carefully, the way one would approach a frightened and cornered animal so as not to spook it, that he’s been in prison for thirty years. His mind is blank as he blinks, the only physical indication of his surprise. According to the prison records, they say, from when they took control of the jail and the surrounding cities. That’s how they found his cell. Thirty years. He nods numbly, looking back up at the sky. It was really blue.

All around him families continue to be reunited—hugging, crying, screaming, laughing, yelling, chanting. Is this what liberation looks like? His head swims as his eyes drop down from the sun and dart everywhere. He is unused to the noise, the cheers of celebration. The silence inside had become his trusted companion. He is unaccustomed to being around others who didn’t want to hurt him, but would rather stand by him and share in their collective pain. The sympathy is alien to him. He doesn’t know what is normal anymore.

Drip.

Another soldier with the green flag—young, maybe fifteen years of age from the softness in his features—jogs up quickly from behind and tries to cover the man with a blanket, but the man flinches away and the young soldier freezes, unsure of his mistake. The man bows his head in shame as the young man gingerly hands him the blanket and helps the other soldiers bring him to the nearest car—he had forgotten about cars. He hesitates again as they usher him inside and assure him that people are looking for him. Family. Friends. The droplets? Nothing makes sense. What pattern should he follow now? He perches on the edge of the seat, his body tense again and his muscles, coiled tight, unable to relax. He exhales a short breath out as his eyes remain trained to the ground. There’s a candy wrapper under the seat in front of him. He tilts his head as he squints at it, trying to determine the color. Red? He bends down further and identifies the color pink. He shakes his head as he leans back surprised. He remembers colors. Do you? He looks up and finds the driver looking at him inquisitively. The man turns his head away to hide his mortification. The driver, ignoring the man’s reaction, clears his throat and informs him that he will take the man, and a couple others, to the closest mosque. The man nods absently, his gaze now caught on a dark stain near the wrapper. He remembers now. Bits and pieces. The soldiers with the red flag—the ones that arrested him—brought him to the prison when he was young. He went to pray Fajr at the mosque. That’s when they took him. Thirty years ago, they said. He slowly starts to remember.

The soldiers—the ones with the green flag—stop him before they close the door. He drags his gaze from the stain on the car floor—where was it from—to look up at them. The one who had greeted him like a brother is looking at him intently, and the man realizes he’s waiting for a response, that they must have been talking to him the whole time. The soldier’s eyes flicker with something indecipherable as he seems to understand and repeats himself. The man peers up at him, trying to keep his mind open to the words this time. Can you teach him how to listen again? The four of them—including the young one—introduce themselves and tell him their names. He opens his mouth to respond and pauses. What’s his name? He stares. Does he have a name? Did you know people still have names? He remembers when they took him but not what they called him. He shakes his head. The free soldiers look at one another worriedly. They tell him his name. He doesn’t recognize it. They got it from his prison record as well. He nods his head slowly and allows them to close the door. Their goodbyes fade into the background as the car begins to move. He closes his eyes. The sun was too bright to look at. He forgot that. Did you? Everything was too bright.

Drip. Drip. Drip.

He has a name now. The guards had only ever used vulgar insults to get him to pay attention. If he didn’t react, they’d shatter a joint. Sometimes they forced him to pick only to do the opposite. If he chose his foot, they broke his hand. He opens his eyes slightly and looks down at his hands, letting go of the blanket he had been gripping as he raises them in front of his face, turning them side to side. He wasn’t used to seeing his fingers. To observing any part of himself so closely—do you also find it unnerving? They were long and slim, bent at the angles at which they were repeatedly broken. He drops his hands back in his lap. His heart stutters at the thought of looking into a mirror, afraid of his reflection. Thirty years. What would he see? What do you see?

He breathes in shakily and shuts his eyes closed again, squeezing them tight. Is this real? He bends forward in the seat, putting his head between his knees. He shrinks his body in to block out all the light from the windows, pressing the heels of his hands into his temples. Perhaps if he keeps his eyes closed long enough he’ll be able to keep count again. He can keep the pace this time. He knows he can. The taste of freedom is unfamiliar to him.

Drip. Drip.

He still hears the droplets.

Drip.

Can you hear them too?

Thank you to Tiernan O’Neal for her assistance with editing and revising this piece. It would not be where it is without her help.