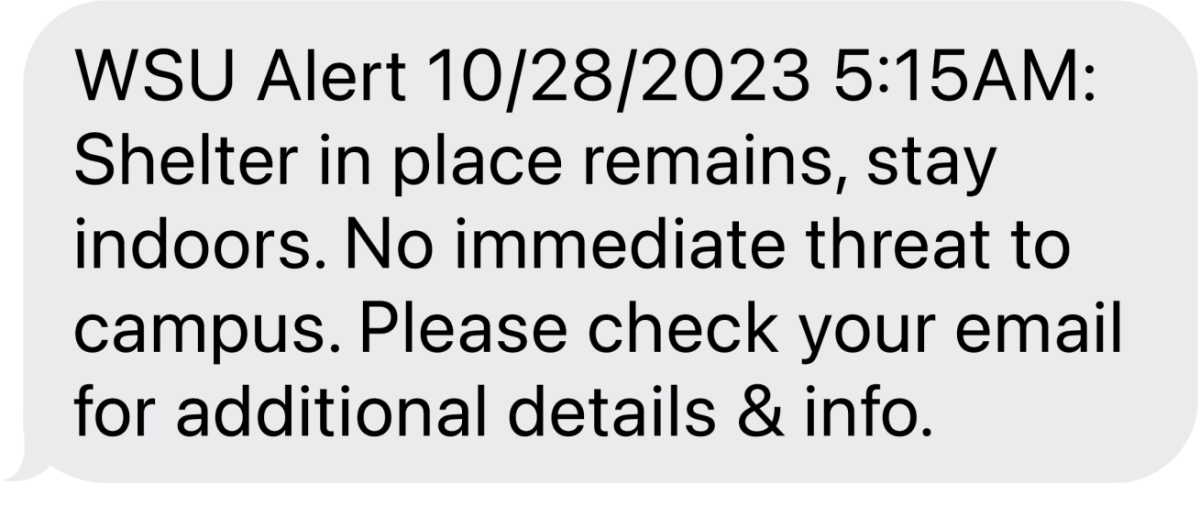

In the middle of the night on Saturday, October 28, 2023, students on and off campus were awoken by emergency calls and texts from the school. They were informed that Worcester State University was going into a state of lockdown and told to avoid all windows. With very little information, their imaginations were left to run wild about what the unstated threat could be. A terrorist attack? A tornado?

The message, stating that “more information will be provided as it becomes available,” was sent at 2:49 a.m.

Renee Mercier, a graduate student sleeping in her first-floor Wasylean apartment at the time, reported how the lack of communication, combined with tiredness from being woken up after just a couple hours sleep, terrified her. Campus authorities were “probably being intentionally vague to keep people from freaking out,” she said, but having no idea what was happening freaked her out more.

She did as she was instructed, taking shelter in the only room she could access with no windows—the bathroom in the interior of her suite. She remembers calling a friend of hers living in Hawaii for comfort, since this was the only person she knew would be awake at that hour (it would have been about 9 p.m. in Hawaii).

Mercier remained on the phone with her friend for a couple hours while sitting in the bathroom with no further communication from the school. An email from the school’s alert system was sent out just after 5 a.m. indicating that while “there is no immediate threat to campus,” the shelter-in-place order was still in effect. A text message indicating the same was received by students around 7:30 a.m. Ultimately, it was from her friend, who had been searching for any information regarding what was going on at Worcester State, that she first learned about the nature of the emergency.

The facts of the shooting are clearer now than they were on that Halloween weekend. Mark Relation, the records access officer in District Attorney Joseph D. Early, Jr.’s office, initially denied the Herald access to records from both campus police and the City of Worcester, pending an investigation. Then in late May, the Herald acquired audio of the 911 calls placed that night.

A brief timeline was included in the Critical Incident Review PowerPoint slides shared with the campus community in August, though some components of the timeline remain elusive.

The following has been established based on releases from Worcester County District Attorney Joseph D. Early, Jr., reporting from other news publications, and video footage of the scene posted to social media.

According to a MassLive article published on December 21, 2023, there were two groups involved in the shooting: a group of six men from Lawrence and a group of four men from Southbridge and Spencer. Both groups attended an 18+ party at Leitrim’s Pub the night of Friday, October 27, 2023. Once the party had simmered down, both groups drove to WSU to continue partying. This was just before 2 a.m.

Around 2:30, after the groups had arrived on campus, they were reportedly doing “burnouts” in the parking lot outside of Wasylean Hall when a conflict arose. According to a Worcester Telegram and Gazette article, the conflict occurred between two of the men from Lawrence and three of the men from the Southbridge group: suspects 18-year old Richard Nieves and 20-year old Kenneth Doelter, and 19-year old Randy Armando Melendez, Jr., who later died from gunshot wounds inflicted that night.

Allegedly the conflict quickly escalated into a physical altercation, which led Nieves to “[retrieve] a firearm from his person and [discharge] the firearm into the air,” as reported from a statement of facts read in a related January 5, 2024 court hearing. According to the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, the statement of facts also revealed Nieves, Doelter, and Melendez, allegedly took one of the men from Lawrence, an unidentified 21-year old man, to the back of a parked truck and robbed him at gunpoint.

According to the MassLive article, 18-year-old Kevin Rodriguez of Lawrence exited a vehicle, ran over to the altercation, and allegedly shot Melendez three times. Rodriguez ran back toward the vehicle as Nieves allegedly shot the unnamed 21-year old victim they had been robbing.

Multiple graphic videos of the shooting circulated social media immediately following the tragedy, including at least one taken from a Wasylean east-facing window and one taken from the parking lot itself, clearly demonstrating the chaos seen on the ground.

Worcester State Police Chief Jason Kapurch told the Herald, “we live in the second largest city in Massachusetts. We had an incident spill onto our campus from a local establishment […] The incident didn’t involve any of our students.”

While this was originally comforting news to some, especially for parents of Worcester State students, some were more critical of how this detail seemed to permeate communication about the shooting and media response.

“It doesn’t matter that it wasn’t our student who died. That’s actually irrelevant,” said Dr. Erika Briesacher, a professor at Worcester State University. “It was still someone who was somehow connected to our community, which means that it is our problem.”

Once police arrived at the scene, the two victims were immediately transported to UMass Memorial Medical Center—University Campus. Randy Melendez died of his injuries while at the hospital. His obituary shared that he was a recent graduate of Southbridge High School in the Class of 2023, had been an avid player on the football team, and had just turned 19 five days prior. While the 21-year-old victim survived, he was paralyzed from the waist down, his life forever altered.

While Nieves was arrested the same day nearby the university, Rodriguez fled and led police on a multi-day hunt.

Around 9:30 a.m., the shelter-in-place order at WSU was lifted, although the texts and emails still hadn’t specified the threat. Mercier had stayed up all night in the bathroom and never got back to sleep. She wishes the university had been more clear about what was going on. “I felt like I should have found out from the school itself, and not from a random news outlet,” she says.

Nolan Lonstein, a commuter student who serves on Student Senate, recalls waking up to the same text message those living on campus received. He also reports being terrified and staying up for the rest of the night.

Friends living on campus at the time had witnessed the event. From them, Lonstein got word before many other commuter students that the unspecified threat had been a shooting. He says he was thankful he knew what was going on but also felt disappointed with the communication from the school. “Leaving many parents and students and faculty in the dark,” he says, “was an immature decision.”

Phillip Seyaki, then a senior living in a Chandler apartment, mentioned that the vagueness of the messaging could also have the opposite effect—many students likely ignored the alert entirely. “Unless you saw what happened or heard it from a friend, you’re not taking that message seriously,” he said. He’d heard about that night’s tragedy from one of his friends who received a phone call about the shooting.

Seyaki said he and a group of friends were later moved to Dowden Hall and made to wait for three hours while police officers searched their apartment. They’d been the subject of an emergency call 25 minutes after the shooting.

Provost Lois Wims, who was then serving as acting president, said in a Campus Conversation on Nov. 28, 2023 that “while a weapon was reported in an emergency call, no weapon was found.”

In Wasylean, Aveen O’Brien, a senior at the time, was also made to wait by police. From her third-story Wasylean window, she had witnessed the shooting and the chaos and violence which had preceded it. She and her friends had just returned from a Halloween party and were still dressed in their costumes.

For about an hour, she’d been waiting to speak with a police detective about what she witnessed. She remembers waiting in the Wasylean lobby until 5 a.m. She said she was periodically heckled and questioned by multiple officers, all the while still wearing her Halloween costume. She said one of the officers had an assault rifle.

She diligently responded to all of the officers’ questions, reporting that the only one she couldn’t answer was what the license plate number on the car of the shooter was. She said the detective was the only officer who treated her with respect.

Though parents were not awoken to emergency calls that night, many woke to an email from Worcester State pertaining to an unspecified “incident” which occurred in the pre-dawn hours. Many had learned of the shooting from social media before the school ever sent out an email.

One parent of a reporter on this story, Valerie Ducey, said that “there was very little substance in the information that was given.” One of Ducey’s biggest concerns at the time was whether students were involved in the shooting. While she learned from outside sources that they were not Worcester State students, she wishes the school had communicated as much.

The shooting led many parents to learn about RAVE Alerts, an emergency messaging system used by the university. Some shared that they hadn’t thought of the alert system as important before the tragedy occurred.

Despite campus authorities’ attempts to contain the tragedy, its impacts were felt beyond campus as well. Adam Mickey, a resident of the neighborhood behind campus, near Patch Reservoir, says he was fearful for his family’s safety upon hearing about the shooting, including the safety of his two-year-old son.

Around eight in the morning, he noticed while driving his son to school that the gates around campus were closed and the cops weren’t allowing people in. Curious and concerned, he scoured the web to see what was going on, but all he could find were vague reports of an “ongoing incident.” He learned an hour or two later that the unnamed incident had been a shooting, but recalls the information was still very vague, and he didn’t know whether the shooter was still in the vicinity or what their intentions were.

“My first thought when I found out it was a shooting was that we’re really close and our neighborhood is pretty quiet, so if someone were trying to run away, they might come towards our neighborhood,” he said.

On campus, many students said there appeared to be no plan or policy in place for responding to such an event. Student leaders and administrators, when asked in the spring of 2024 if we’d be better prepared should a tragedy like the Oct. 28 shooting happen again, gave diplomatic answers. “I think that’s our duty and our responsibility,” said Kevin Fenlon, a counselor.

In January, 2024, Lonstein joined WSU’s Incident Review Committee charged with reviewing the university’s response and follow-up actions to the campus shooting. “I think we will be better prepared than we were in October,” said Lonstein, after taking a long pause.

On the Saturday and Sunday following the shooting, the university canceled all events, including Family Day and Homecoming, and decided last-minute to cancel all classes on Monday.

After Monday, however, professors found themselves lacking direction from the university, which led to inconsistent responses to the shooting throughout departments. Some professors canceled classes for the remainder of the week, while others held classes but spoke about the shooting and offered support or promoted the Counseling Center and other relevant resources on campus.

Moreover, some professors were very lenient about attendance in the weeks following the shooting, or liberal about granting extensions for assignments. Quinn Willshire-Rodgers, then a sophomore who witnessed the shooting from his Wasylean window, said that his professors “all handled the situation really gracefully.”

In addition to the lack of communication from the university, many students were frustrated by the security policy which was implemented shortly after the shooting.

On Nov. 1, 2023, the Office of Residence Life and Housing announced a change to the security policy in the residence halls which would go into effect at 5 p.m. that night. All students entering the halls between 5 p.m. and 8 a.m. were required to provide their student ID to a security officer working near the doors to the elevators. No outside guests were allowed during these hours, even residents from other halls.

Chandler Village was excluded from the policy, as university officials reported that it would have been too difficult to enact for the individual apartment buildings.

Many students were frustrated by this security change. The security measures “seemed a little out of place,” Mercier said, since the incident didn’t happen in the residence halls. “It was more of an inconvenience than anything.”

Willshire-Rodgers said, “When guests weren’t allowed, it felt more like a punishment to the students that lived on campus” than anything else. Other students say the measures were purely performative.

The security policy was not announced via email or text, so it caught many students by surprise. With no other place to go, groups of friends, residents from mixed halls, and commuters crowded into the Student Center for the rest of the week. Students recall there was nowhere to sit. Every seat on all three floors of the building had been taken.

By Monday, November 6th, typical guest policy was restored, allowing for two guests per resident during nighttime hours. These guests could stay for up to 48 hours, and would not be allowed back in during the same one-week period. Students could swipe in with an RA between the hours of 5 p.m. and 1 a.m., but would still have to provide their ID to a security guard between 1 a.m. and 8 a.m. Before the shooting, students said, standard policy was not enforced so they had been able to come and go as they pleased during all hours.

The security guards were removed at the end of the fall semester, while the rest of the policy remains in place.

The university also increased police presence on lower campus in the weeks following the shooting, which students had mixed feelings about. Brianna Remy, then a senior commuter student, reported this increased presence was a comfort. Willshire-Rodgers said he doesn’t think it “did much other than make people nervous.” Parents reported feeling that the extra police presence wasn’t enough.

A new security system was implemented at both the North and South entrances to scan the license plates of incoming vehicles. WSU announced in advance that the plate reading technology was set to be fully operational at the start of the spring 2024 semester, allowing the university police department to log and document vehicles entering campus. This system typically helps law enforcement in missing persons or abducted children cases, but it can also be used for both safety and investigatory purposes on the university campus.

…

On Monday, October 30, 2023, Nieves and Doelter were charged with armed robbery and aggravated kidnapping. Nieves was also charged with armed assault with intent to murder, assault and battery with a dangerous weapon causing serious bodily injury, discharging a firearm within 500 feet of a dwelling, possession of a loaded firearm not at home or work and possession of a firearm not at home or work as announced in a December 21, 2023 release from District Attorney Joseph D. Early, Jr.

Police found and arrested Rodriguez on Nov. 2 in New York. According to Boston 25 News, Rodriguez signed a waiver of extradition once captured and was transported back to Massachusetts. On Nov. 9, Rodriguez was arraigned and pleaded not guilty in Worcester District Court.

In court that day, Melendez’s father told Boston25, “I’m lost. I have no idea what happened. How it happened. This is devastating to me, my family, to everybody that loved him.” He added, “it was his birthday weekend, just turned 19 on Monday. [He] went out for the weekend to celebrate. And then all this happened.” When asked why he was in court that day, Melendez, Sr. said that he wanted to “see the face of the person who did this to my son. That’s why I’m there. And I’m going to be there, every time no matter what.”

The cases are still winding their way through the legal system.

Among controversy, Worcester State University hired external consultants from the Healy+ Group to work with the Incident Review Committee and provide recommendations for university procedures and practices. Their report is complete and currently available to be viewed by appointment only. The Herald’s repeated requests to access the report have gone unanswered.

The bloodstains remained for a week after the fatal shooting, undisturbed by police or crime scene clean up crews, until they finally washed away with a heavy rain. While the shooting was still fresh and constantly in the backs of students’ minds, the erasure of the blood by the rain brought relief. One student whose path took her through the parking lot only days later braced herself by closing her eyes, then ran past the blood as fast as she could, unable to bear the sight of it and the reminders of the tragedy that unfolded on campus just outside Wasylean windows.